Next weekend (29 October 2023) we will once again be putting our clocks back and the dark nights will be upon us until we put them forward again at the end of next March.

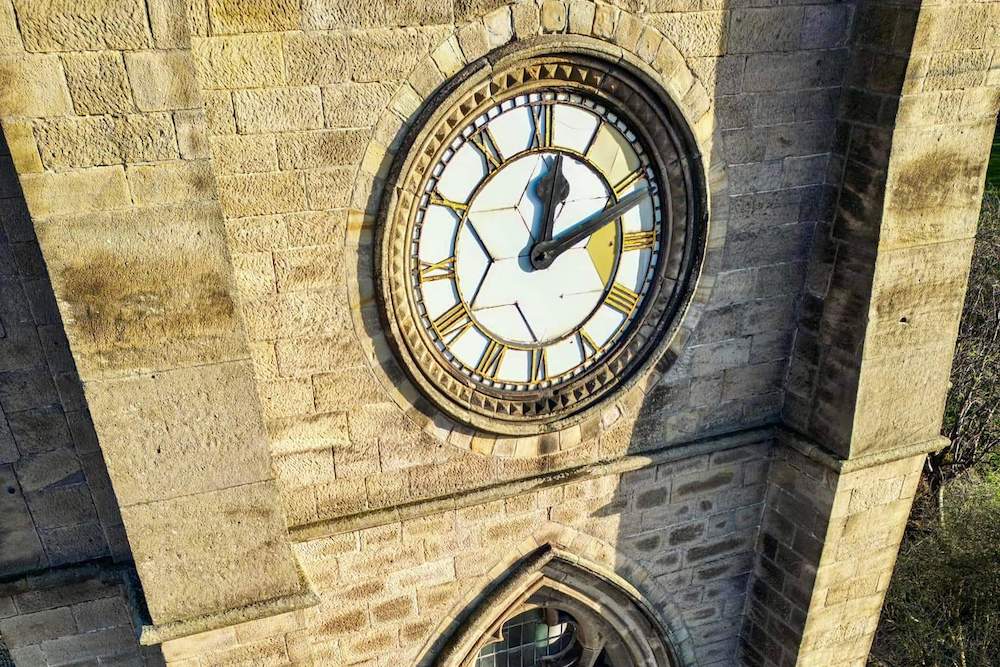

I have already written an article for South Leeds Life arguing that it should be end of February not March to put them forward again for us to have lighter evenings and saving energy so will not go into those arguments for that again. But it has set me thinking about the importance of public clocks such as St Mary’s Spire in Hunslet.

Until the railways came along in 1840, time was different in different parts of the country. It was impossible to fix a railway timetable especially for journeys east to west. The Great Western Railway running from London to Cornwall was the first to introduce “Railway time” and other rail companies followed. By 1847 most but not all of the UK operated on Railway Time.

But Railway Time was not declared to be legal until 1880 when following a notorious court case which depended on the accuracy of time given by witnesses, the judge declared that the times given were not legal and the trial could not proceed. The Government then passed an Act of Parliament requiring the whole of the UK to adopt Greenwich Mean Time. (British Summer Time was not introduced by Parliament until much later in 1916.)

Churches were, perhaps the forerunner of providing public clocks as it was essential that people knew the time of service as parishioners could not roll up at any time. The clock on the listed St Mary’s Church Spire in Hunslet dated 1864 most probably operated originally on the widespread acceptance of Railway Time. But public buildings such as the Moot Hall in Lower Briggate also had clocks on them. Mills and factories also spawned clocks not just to inform their employee workers of the time but also as status symbols and as advertising aids.

Public clocks remained very important for people to know the time for well up to just after the Second World War as mechanical household clocks and watches were a very expensive item and were not always reliable. My childhood memory was of having one clock in the house which served as a mantel clock during the day and was taken upstairs at night by Dad to function as a wake-up alarm. Very occasionally, the alarm did not go off and the family slept in! This caused great consternation as being late for work was very serious. One not only lost money but also if it were a regular occurrence then the worker could be dismissed.

Many workers who lived in terrace streets paid for a “knocker-up” which was cheaper and more reliable. Knocker-ups were usually men but there were a few women who tapped on bedroom windows with a long thin cane. This method was used up until about the early 1950s when the last knocker-up in the UK retired.

And wearing one’s own watch, because of the expense, was not frequently done. When I was eleven years old I was, like most children, asked what I was getting for Christmas. I remember saying with pride, “A watch”. That watch lasted me through secondary school and into adulthood when I wore it for work. But it was not totally accurate and going to work on the bus I passed five public clocks on various mills and factories and I was always checking the time.

Bigger pocket watches worn mainly by men were more accurate, but it seemed to me even then that they were worn by men as status symbols especially if they were suspended on a gold chain with fobs of gold sovereigns or semi-precious stones. Pocket watches began to fall out of favour mainly with the onset of the First World War when they could not be worn with uniform and certainly the Second World War when men who were on active service, needed to know the time and needed to quickly glance at a wristwatch and not have to fiddle about in pockets.

Watches and clocks these days are mostly run by battery and do not have to be wound up and are very accurate. Some are radio controlled like the very cheap clock I have in my bedroom which automatically puts the clock back or forward dependent on the time of year. Just about everyone now can afford as many clocks or watches as they wish. But some people do not bother with them at all and totally rely on their mobile phones to let them know the time of day and use them for wake-up alarms.

So what is the future of our public clocks? Many of our big public clocks have disappeared as the buildings on which they were on have been demolished. Those that remain are on buildings which are listed such as the one on Hunslet St Mary’s Spire and, of course, our famous Town Hall and adjacent Civic Hall, the Corn Exchange and the Art Deco clock on the Queens Hotel.

Perhaps the most famous clock in Leeds is the listed one outside former Dyson’s jewellers in Lower Briggate. On the hour a ball dropped down. For some reason it became a favourite place for courting couples to meet up “under the ball”.

We have the entertaining clock in the Grand Arcade (1897) looking like the front of a castle with a knight in armour each side of it striking the quarters. Then, on the hour, five figures emerge out of a door at one side of the castle and either salute or bow and then disappear through a castle door at the other side of the clock.

And there is Thornton’s Arcade with the beautiful clock (1877) where characters from Sir Walter Scott’s novel “Ivanhoe” – Robin Hood, Friar Tuck, Richard the Lionheart and Gurth the Swineherd, strike bells on the quarter and strike a bigger bell on the hour. Both clocks were built by the famous Leeds clockmakers, Potts and Sons.

But big public clocks do not have to be entertaining to be enjoyed or appreciated by all whether or not wearing a watch or carrying a phone. They give us a sense of place and ownership. Our UK Government thought so by spending many millions on “Big Ben” at their place of work in Parliament. It saddens and grieves me that our much-loved clock at Hunslet St Mary’s has been silent for seven years awaiting stonework restoration to the spire, and despite Hunslet & Riverside councillors (which included myself) setting money aside for its restoration. Let us hope that we will be able to hear the chimes of St Mary the Virgin again soon.

This post was written by Hon Alderwoman Elizabeth Nash

While you’re here, can we ask a favour?

South Leeds Life is published by a not-for-profit social enterprise. We keep our costs as low as possible but we’ve been hit by increases in the print costs for our monthly newspaper – up 83% in the last 12 months.

Could you help support local community news by making a one off donation, or even better taking out a supporters subscription?

Donate here, or sign up for a subscription at bit.ly/SLLsubscribe