Every year on the 27 January the world marks Holocaust Memorial Day. It is the occasion when we remember the six million Jews and others who were murdered by the Nazis, and all those who were killed in more recent genocides in Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia, and Darfur. It is by continuing to remember that we can ensure that we never forget.

Given the scale and monstrosity of these crimes, it may seem extraordinary that there might be any possibility of forgetting. But those who can speak about what actually happened in the Holocaust are getting fewer and fewer in number and as they pass away, their truly shocking first hand testimony about how new arrivals at the concentration camps were separated into two groups – those who would be set to work and the rest who were marched direct to the gas chambers – dies with them. And sadly, as we live in a time of denial and distortion of the Holocaust, as some choose to doubt the evidence of those who were there. More recent genocides are also denied or disputed.

As we read the history books, listen to the accounts of survivors and visit places where these terrible events occurred, we struggle to understand how people could have done these things to their fellow human beings.

Populism, political extremism, hatred and searching for scapegoats bear principal responsibility, but it is also true that genocide is made possible by ordinary people who look the other way, believe the lies or simply say “I was only carrying out orders.” And those who are murdered haven’t done anything; they have simply been made the target of someone else’s hate.

In 1994, over a period of about three months, around 600,000 members of the Tutsi community were killed by armed Hutu militias and others. When I was the International Development Secretary I visited a prison in Rwanda that was full of genocidaires – as they’re called – who had carried out some of the killings. A man told us he had been a school teacher and was one day forced to participate in the murder of complete strangers in fear for his and his family’s life.

“I took part in the killing of three people” he said.

I will never forget that moment. Did I believe his story? What would any of us have done in the same circumstances? Where did this terrible hatred of friends and neighbours come from?

A few years later I visited Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Remembrance Centre in Jerusalem. Three memories of that day stand out. The exhibition about the Holocaust which made me weep with sorrow and boil with anger. The Avenue of the Righteous Among the Nations which remembers non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews by hiding them in their homes or giving them false papers. And the Children’s Memorial, hollowed out from an underground cave, which remembers the approximately 1.5 million Jewish children who perished during the Holocaust. As you walk through it, you hear the names of the murdered children, their ages and where they came from in the background. No parent can stand there without thinking of their own children.

I have been to Darfur and talked to villagers who were burned out of their homes and I have heard testimony from a young man who was in Srebrenica in 1995 when his brother and father were led away with around 8,000 other men and boys to be murdered by the Bosnian Serbs under the command of Ratko Mladić. Mladić was later convicted of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

And that is why the International Criminal Court is so important. It collects the evidence and subjects it to thorough examination in pursuit of the truth which those who commit these awful crimes wish to hide away in the darkness.

All of these stories and many more are heart breaking but they are the reason why we must remember so that the history of some people’s inhumanity can be passed down the generations. Why is this so important? Because it is the best protection against it ever happening again.

So much for the worst of humankind. What about the best? 35 years ago a remarkable television programme was made about a man called Sir Nicholas Winton who had rescued 669 mostly Jewish children from Czechoslovakia before the outbreak of World War 2 and brought them to Britain. In the intervening decades he had barely spoken of what he had done. He was sitting in the studio with his wife when suddenly the presenter asked if there was anyone in the audience who owed their lives to Sir Nicholas. Everyone around him stood up. Unbeknown to him, they were the children he had saved 50 years earlier.

This unassuming, bespectacled man sitting in the front row was completely taken by surprise, and the children – now adults – gazed upon the saviour who had given them life. This is what humanity means and this is why it is only fitting that he is one of those remembered in The Avenue of the Righteous Among the Nations.

This may all seem rather far away, in time and distance, from South Leeds but in recent years our community has provided shelter to many people who have been forced to flee the land of their birth by war and political persecution. It is the very least we can do to help them as they make their lives and their futures among us. After all, if it was us, would we not wish to be taken in and welcomed in the same way?

Whilst you’re here, can we ask a favour?

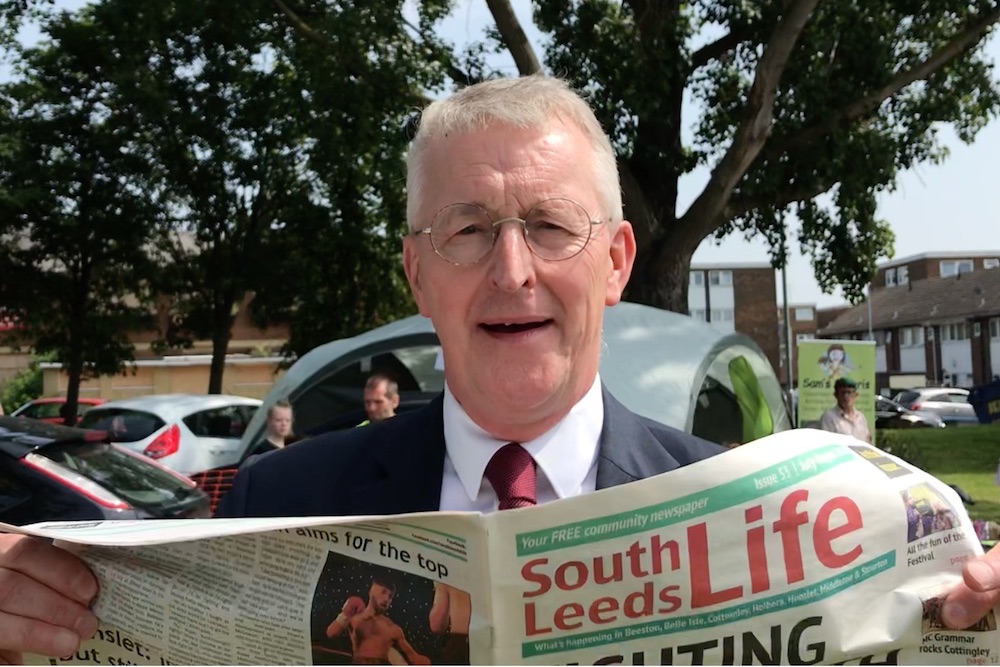

South Leeds Life is published by a not-for-profit social enterprise. We keep our costs as low as possible but we’ve been hit by increases in the print costs for our monthly newspaper – up 50% so far this year.

Could you help support local community news by making a one off donation, or even better taking out a supporters subscription?

Donate here, or sign up for a subscription at bit.ly/SLLsubscribe